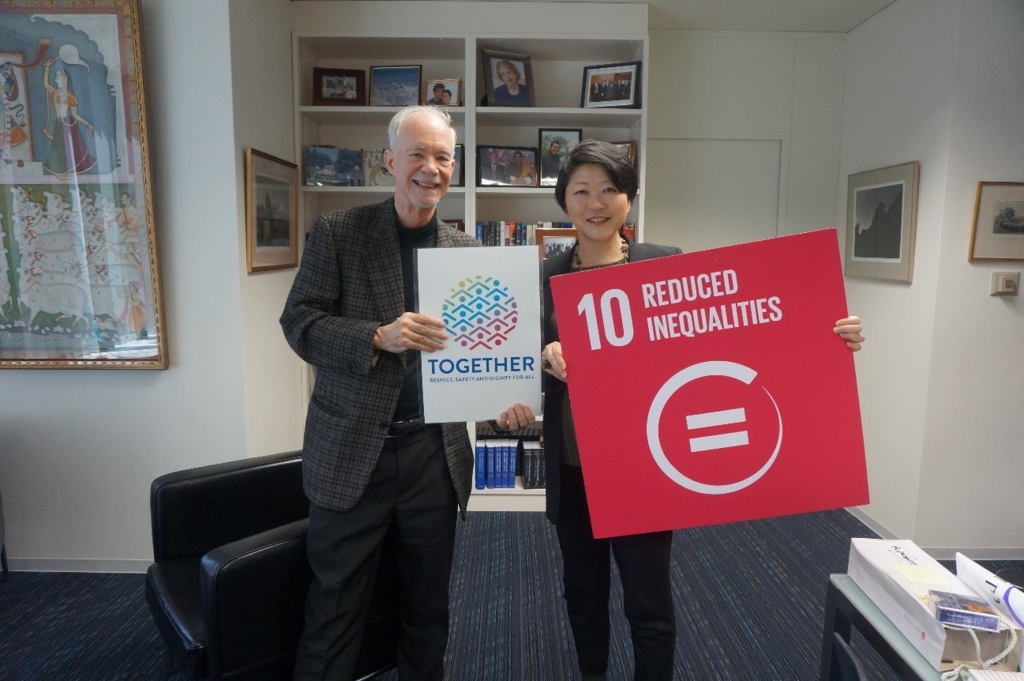

TOGETHERキャンペーンの一環として、この度、グローバル・マイグレーション・グループ(GMG)議長を務めるデイビッド・マローン国連大学学長(国連事務次長)にお話を伺いました。GMGとは、国際移住機関(IOM)や国連難民高等弁務官事務所(UNHCR)を含む22の国連機関が集まるグループです。今年は、2018年秋に合意を目指す移民のためのグローバルコンパクトの基礎を整える活動を行っています。また、世界中で移民が重要な政治課題となっている現状を踏まえた上で、SDGsのゴール10(人や国の不平等をなくそう)にも関係する社会的排除を根絶するための取り組みなどについて、貴重なお話をお聞きしました。

(聞き手:国連広報センター所長 根本かおる)

Kaoru Nemoto (KN): Thank you so much for being with us today. You’re holding the chairmanship of the Global Migration Group (GMG) at a very critical time.

David Malone (DM): Well, happily, the 22 agencies and funds and programmes plus the Secretariat who participate in the work have already set a very different work programme, for this year at least. What we are trying to do as a group of agencies is help member states negotiate the best possible compact on migration in 2018. That is our only purpose in 2017 and 2018 and that is the fundamental change that was agreed amongst us in February of this year, after a very frank dialogue amongst us.

In all organizations there is a tendency to go on doing what you’ve been doing because you’ve been doing it. But what changes everything is the decision taken last September 19th at the summit level, of the Member States to negotiate two compacts, which may or may not be binding, probably not, but still engage their responsibility. One is on refugees and it’s important because there are so many refugees in the world today. But it’s probably an easier exercise because we already have a number of agreements on refugees. Indeed, the agreements that underpin the activity of the UN High Commissioner on Refugees have shown us the way and it may be possible to add to those. But we already have a good body of agreements that is widely subscribed.

On migration we have nothing; I shouldn’t say nothing because there is the Domestic Workers Convention and that’s very important because we know so many individuals, often women, travel the world in order to support their families back home, working as domestic workers, and have very often been treated shoddily in other parts of the world; basically not accorded their rights or even often paid what they were owed, had their passports confiscated, and all sorts of other unacceptable practices. There are also the Migration for Employment Convention and the Migrant Workers Convention. So we have these agreements and they discuss very practical matters, helpfully. But overall there are few agreements.

During the opening of the UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants, Secretary-General Ban-Ki Moon seated right) and William Lacy Swing (seated left), Director General of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), sign the agreement to make the IOM a Related Organization of the UN. © 2016 United Nations

But there are a number of very dedicated NGOs internationally, as well as a wonderful international organization called the International Organization for Migration, Geneva based. It’s a very low cost, high-impact organization that focuses on the migrants. It doesn’t focus on chat, it doesn’t focus on international politics, and its only concern is service to the migrants. Not surprisingly, they are very well supported by funders because unlike so many agencies, they’re clear about what they’re doing, why they’re doing it, how they’re doing it and they do it at low cost. What’s not to like? So importantly, I mention IOM because it had always been an agency quite independent from the UN system, working with the UN quite often, occasionally sitting with the UN, but legally it had nothing to do with the UN. On September 19th at the Member States of the UN at the head of government level decided to invite IOM as a related organization. Nobody is quite sure what that means, but it brings IOM into the organization and that is very good. So the GMG, of which IOM was already a member, needs to adjust to the fact that IOM is now in the UN system, and this is a very good thing in my opinion.

There are many reasons for the GMG to change its work programme but I’d say the two immediate stimuli were that the Secretary General and his new Special Representative, Louise Arbour, needed support from the agencies to do their work to help the member states in negotiating a compact on migration. Secondly, the President of the GA also reached out to the GMG on how we could help delegates and government representatives in New York and Geneva educate themselves more, not on how we can negotiate agreements, but on migration itself. Most of us know much less than we think we know on migration. I come from a country of migration, both in and out. There are probably three million Canadians abroad at any given time and we have many non-Canadians in Canada; for us that’s a very good thing.

Japan funds IOM humanitarian projects worldwide. © 2017 IOM

But if we were to ask even very knowledgeable people, frankly I think we would get about 1% at best of semi-accurate responses. I realize that also was the case for me after I realized that I would be chairing the GMG this year. Being a researcher myself, my first question was what do I know, and frankly the answer was too little, and of course, the more I’ve tried to learn, the more I realized I don’t know, because learning is a never-ending process and that’s why the GMG, with the expertise of the various agencies, funds and programmes, also the variety of opinion within this group of agencies can be helpful, and I’m not sure it had been so helpful in the recent past. Indeed, we were told at our retreat in February of this year, that Member States had been quite disappointed with the output of GMG and that was helpful for the agencies to hear, and also for me to hear. If our clients are disappointed that’s something you don’t want to ignore and we can change, because these are excellent agencies and funds and programmes, all with specific knowledge, specific programmes that are very valuable.

We were lucky because the previous chair of this group was UN Women, and they are a fairly small agency like UNU, but they have a very dedicated team working on this. They have done a good job of preparing us; if we hadn’t had the partnership of UN Women and some very solid research work the previous chair, the World Bank had done, we probably would not have been able to achieve what we have achieved so far, which is just a modest beginning of how GMG will probably wind up working in the long run. Nearly all individuals, certainly all organizations, are very resistant to change. So we needed this new stimulus from member states, from the Secretary General, for the agencies to understand that actually good enough isn’t good enough- we needed to be better and more focused and more responsible to what the member states actually needed.

Fifteenth Coordination Meeting on International Migration 16-17 February 2017 United Nations Headquarters, New York (David Malone - second from the right) © 2017 United Nations

KN: Yes, I looked at the draft resolution for the modalities and it’s really packed!

DM: It is very packed, it may be over packed in fact, but what I like about the process is it’s at regular intervals. Many of the delegates are already quite well informed on some aspects of migration, so I think the way the process unfolds this year, which is a preparatory process, is that the member states will not be negotiating this year - they’re simply trying to prepare themselves. So in that sense having, if anything, too much activity is probably better than having too little. I think that was the thinking of the President of the GA and the two co-facilitators who were the ones who largely shaped the resolution - you’re mentioning the ambassadors of Mexico and Switzerland, both very accomplished actors. I think they felt more may be better than not enough because the challenge is a very significant challenge and not everybody in the UN realized how significant.

KN: Indeed, there is strong reaction of xenophobia in many parts of the world, and you talk about the importance of knowing facts. There are negative myths about migration, and it’s really important to know these facts and have analyses of the data.

DM: But also to allow countries a forum in which to compare their national experience. Because the absence of facts, but also the absence of understanding how other countries have successfully benefitted from migration is important. For one thing, activists sometimes distort reality too. When I think of my own country, Canada, the first generation immigrants to Canada, the parents, have nearly always suffered a lot, including in Canada, after they settled. They often left behind good jobs in their own countries for which they were qualified. They come to Canada, find their qualifications don’t meet Canadian standards, wind up having to take jobs that they would never have considered in their own country. Why do they do this sometimes? Simply for their children or other family members to be safe, but nearly always, they have in mind the education of their children.

The positive aspect of what the Canadian example shows is not that we treat our immigrants so fantastically, frankly that is a Canadian myth, because for example doctors who have migrated to Canada have been very actively discriminated against by the Canadian professional associations of doctors who wanted to protect all the business for themselves. Only recently, with governments threatening the Canadian doctors to stop doing this, because there is now a shortage of doctors, are we seeing a more sensible approach by the doctors’ guilds, who are also responsible for certifying new practitioners. Governments started threatening to take away the certification process, and, oh! The doctors’ groups noticed that!

The good thing about the Canadian experience shows that while the parents suffer, and their standing falls, their qualifications often aren’t accepted, they find it difficult to meet the standards of the new country, the kids tend to do very well. I’ll give you an example of a family I knew in Iran who came to my country during the 1980s, the father had been in the hospitality business as a very good chef, and the children had a good basic Iranian education.

The only reason the parents wanted to come to Canada was to educate their children better - they poured all of their resources into that, it paid off very well. All their children are professionals, so the children managed to jump a socioeconomic level because the parents were willing to sacrifice themselves. That is often the story of migration that isn’t told very much. So the idea that every migrant does brilliantly in Canada is simply not true, but they’re willing to put up with the hardship in order that their children prosper. Parents are very altruistic towards their children and other family members even if they aren’t towards the wider public and so that is quite important.

KN: The other day, I went to a seminar organized at the Canadian Embassy, it was about private sponsorships of refugees in Canada.

DM: I think the system of sponsorship is a great one. It was tried first for the Vietnamese boat people, because the government didn’t know how many it wanted and they thought, one way of defining how many we want is by insisting that anybody who comes be sponsored and the public response will determine how many boat people come. The public response was much more generous than the government thought, a bit to the distress of the government because all of this was costing a lot.

Ethiopian migrants who had been evacuated from Hodaidah, Yemen, are received in Djibouti Port by IOM staff. © 2016 IOM/Natalie Oren

But it worked, that’s the basics of it. But even sponsorship has a problem - when you sign up to sponsor you sign up for a year. You really work hard you give a tremendous amount of your time, you help newcomers negotiate all the problems that arise. But it’s a one year contract; what do the newcomers do after the year? How do the sponsors prepare them for being on their own? That transition is actually, emotionally, a very difficult transition on both sides and for the newcomers it’s very different. However, when they have children, after a year, because the kids are so adaptable compared to the parents, the kids are able to help the parents more. Language, also customs, they pick it all up at school in ways that adults have great difficulty because the brain starts deteriorating at the age of 17 and the arteries harden in our 20s –laughs–, so kids are the ones who adapt easiest and best.

KN: You are a migrant at the moment; I used to be a migrant, as a UN official working away from Japan, and migration is something that can happen to you and me, to everybody, and we can be a migrant any day.

DM: Indeed. And you know, some countries take that for granted. For example in Canada, we have a rough balance by the way, the number of foreigners studying, working in Canada and the number of Canadians abroad. But it’s a huge number. Other countries, for cultural or other reasons will never be comfortable with that large a group of foreigners in their midst; they will feel that somehow it is altering aspects of their culture and challenging their preferences in ways that make them feel uncomfortable. I think we have to respect that- we have to respect each country and how it is while rejecting xenophobia, comprehensively, because it is not the fault of the foreigner if the culture has reservations, but it is something that those of us that are engaged with international processes of migration have to accept and understand- that no two countries are exactly alike.

KN: Yes, every country is unique in how it perceives migration and deals with it. But when you look at the situation in Japan at the moment, there is a new initiative arising, for example, an NGO in Japan is now trying to sponsor Syrian refugees in Japan based on the experience of Canada. Also, the number of foreign residents in Japan is growing, while the proportion is still very small.

DM: But it’s growing much faster than people think in Japan, because in Japan, first of all, to live here is to know how many foreigners are actually in Japan. But they’re categorized in different ways. For example, many foreigners work in the agricultural sector in Japan as “technical interns” as part of the Technical Intern Training Program which aims at transferring skills through OJT to people from developing countries for a certain period of time as part of contributing to developing countries. The maximum duration of training period increased up to 5 years with the passing of a new law in November 2016 which also includes establishment of a special organization responsible for the investigation and inspection in relation to the technical intern training. Japanese agriculture would collapse without them, and this is not explained in Japan to the public because the government doesn’t want to inconvenience the public by challenging some of the deeply held myths in Japan. If you consider agriculture and its products sacred, then the reality that much of it is being produced and processed by foreign hands might upset some people. Why upset electors?

So there are in fact more foreigners in Japan very usefully occupied, well treated on the whole, because Japan does treat the migrants in Japan much better than most countries do. And this is not sufficiently understood in Japan or outside Japan. As a foreign resident here who enjoys being in Japan, who travels a lot in Japan, who sees how enthusiastic the foreign students in Japan are about being here, including from countries whose governments have a difficult relationship with the government of Japan, say Chinese students or Korean students, they’re extremely enthusiastic about their experience here. But these are things that for societal reasons the government just doesn’t talk about in great deal. Indeed, the business model of many Japanese universities relies and will increasingly rely on more foreign students. But please don’t inconvenience us the public or if you’re the government, please don’t inconvenience the public with this reality.

KN: When we look at the SDGs, its slogan is “No One Left Behind”, including migrants. Goal 10 specifically talks about migration.

DM: Yes, for the first time really, it has arisen as a big issue.

KN: The UN has embarked on a multi-stakeholder campaign called TOGETHER for respect, safety, and dignity for all, which the UNU is part of. We hope to highlight stories about positive contributions by refugees and migrants to our societies in order to engage the Japanese public, in particular the youth.

Children from undocumented returnee families at the IOM Reception Center near Spin Boldak border, Afghanistan. © IOM 2017

DM: I’ll give you one example from my country. Although I’ve spent most of my life outside Canada I’ve never of course stopped being Canadian just as you wouldn’t stop being Japanese no matter how many years you’ve lived abroad. There was a newspaper essay in our best national newspaper, early in the most recent crisis level migration flows. And it was from the Chairman of the Human Rights Commission of one of Canada’s less populated but very interesting provinces, Newfoundland, which is halfway between Toronto and Ireland; geographically it’s closer to Ireland than to Toronto. And it used to be an independent country by the way and joined Canada only in 1949, I think.

So who is this person? This person is an Albanian born person, probably from parents who were at least middle class, probably even better than that. He had the best education possible in Albania, but still for a variety of reasons, he felt marginalised in his society, and wanted to be somewhere else. And one of the reasons he was marginalised was that he was gay in a very conservative society. So he somehow got himself to Canada, he had no money, but there was an openness to him. He went to university, he did extremely well, he professionally, started doing very well. People woke up and thought gee, this guy actually knows a lot about human rights because he suffered a lot from a deficit in human rights! He was appointed chair of the Human Rights Commission, an extremely popular appointment in Newfoundland. He was probably about only 34 when that happened, and he’s been a fantastic chair because when he talks about human rights, he knows what he’s talking about because he suffered from an absence of them early on. So he speaks about it with feeling, but also with sensitivity to how difficult migration is, how one person’s definition of basic human rights may be different from another person’s definition.

There you have a story of somebody who’s been very successful, who started out facing a number of problems but had the advantage of a good quality education. But also, who had the advantage of being single and making decisions only for himself. For parents everything is much more difficult because they have children and they’re responsible for those children. So I don’t want to make it sound easy as I started out saying, it’s very very difficult migrating, migrating in forced migration circumstances, when there’s famine, war, political repression. When some other factor, sometimes ethnic considerations, cause people to migrate, their circumstances are exceptionally difficult. We need to be more aware of this, we need to respect them as human beings just as we are human beings.

We won’t be able to help everyone, but we should all, as citizens of the world, try to be supportive to other citizens of the world that we can help, if we can help them.